Learn More

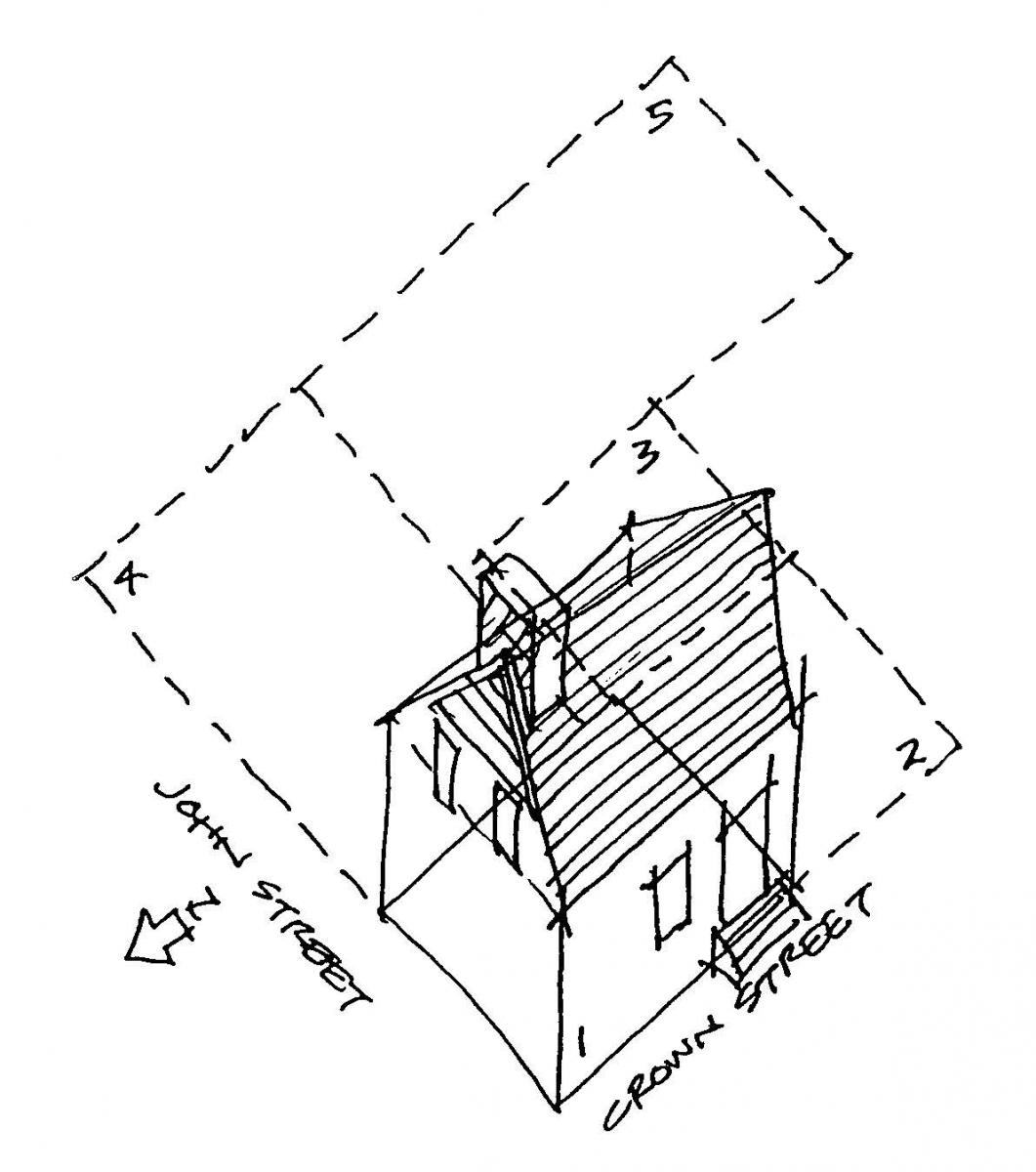

Phase 1 (c.1661-1669) Downstairs

Entrance Halls

The original structure of Phase 1 was only a single room, and would not have had a separate entrance hall. The wall with the door was probably constructed sometime after the mid-1670s, which is when the British seized control of Wiltwyck from the Dutch. Entrance halls were very fashionable in England at the time and so, as English culture seeped into this Dutch colony, some people began creating these halls in order to give their homes a more trendy, modern feel.

Entrance halls have been a part of architectural design for centuries, but their use and popularity have varied over time and across cultures. In ancient times, they were often used in Greek and Roman architecture to separate the outside world from the private spaces inside. Medieval castles and manor houses in Europe also typically had entryways or gatehouses as a means of defense.

However, it was during the Renaissance period in Europe (14th-17th centuries) that entrance halls became more commonly used in residential architecture. In this era, this feature began to be used as a way of displaying wealth and social status, with grand foyers and vestibules featuring elaborate architectural details and decorations.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, entrance halls had become a standard feature of many Western residential buildings, particularly in the United States and Europe. With the rise of the middle class and increased focus on domestic comfort and privacy, entrance halls became more functional and less ornate, serving as a transitional space between the public and private areas of the home.

Esopus Wars

The Esopus Wars were a series of conflicts that took place between Dutch settlers and the Esopus tribe of the Lenape people in the mid-17th century in the area that is now known as Ulster County.

The first Esopus War began in 1659 when a group of Dutch settlers arrived in the Esopus region and began to establish farms and settlements. Tensions quickly escalated, and the Esopus attacked the Dutch settlements, killing several settlers and destroying their homes and crops. The Dutch responded by launching a military campaign against the Esopus, burning their villages and crops and capturing many of their people. The conflict continued for several years, with both sides committing acts of violence and retaliation against each other.

In 1663, a treaty was signed between the Dutch and the Esopus, bringing an end to the first war. However, tensions between the two groups remained high, and in 1667, a second Esopus War broke out. This conflict was shorter and less violent than the first, and ended with the Esopus being forced to cede more of their land to the Dutch.

The Esopus Wars were significant in the history of colonial America, as they were one of the earliest and most sustained conflicts between European settlers and Native American tribes. The wars also had a profound impact on the Esopus tribe, whose population was greatly reduced as a result of the violence and displacement.

For further information on this topic and the Esopus people, we recommend the following resources:

- Journal of the Second Esopus War by Capt. Martin Kregier. With an account of the Massacre at Wildwyck (now Kingston) the names of those killed, wounded, and taken prisoners, by the Indians on that occasion. 1663 (original manuscript), 1910 (printed version translated from the original Dutch), 2021 (digital edition). https://archive.org/details/JournalOfTheEsopusWar/

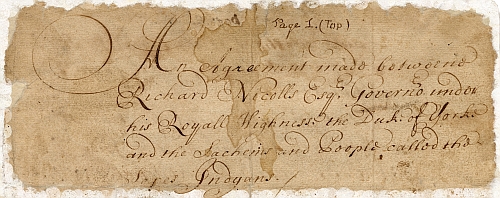

- Nicolls/Esopus Peace Treaty of 1665

- The Story of the Esopus Natives and their Encounter with European Colonialism Curriculum Guide

- Ruttenber, E. M. (1992). Indian tribes of Hudson's River to 1700 (Vol. I). Hope Farm Press. (Available to view in the Archives Reference Library at the Ulster County Records Center, 300 Foxhall Ave., Kingston)

Root Cellars

A root cellar is a type of underground storage area that served many purposes in the past, including keeping food fresh for extended periods of time. It was a common feature in many rural homes and farms before the advent of modern refrigeration techniques.

Root cellars were primarily used to store root vegetables such as potatoes, carrots, and turnips, which could last for months in a cool, dark environment. The temperature in the cellar was typically between 32°F and 40°F, which was ideal for keeping food from spoiling in the summer and from freezing in the winter. Aside from root vegetables, root cellars could also be used to store other food items like salted meats or fruit preserves.

Root cellars were often constructed with a dirt floor, which helped to maintain humidity and prevent the food from drying out. In addition, the walls and roof of the cellar were often made of thick stone, brick, or earth, which provided natural insulation and helped to regulate the temperature.

Today, root cellars are less common due to the prevalence of modern refrigeration techniques. However, some people still choose to build and use them for storing food, as they provide a low-energy, sustainable way to keep food fresh for extended periods of time.

FEATURE: Fireplace

In the original wood structure, the fireplace would have been located where the mantelpiece is leaning against the wall in the picture above. However, the fireplace was moved to its current location circa 1669 when the second phase was added. Fireplaces and chimneys served as important structural pieces, so one possible reason why this one was moved was to create structural symmetry with the new fireplace in Phase 2.

FEATURE: Hinges and Hardware

Original cast iron hardware on doors in colonial houses is a significant feature of the architectural and historical heritage of the country, representing the craftsmanship and durability of the colonial era. These hardware pieces, including door knobs, hinges, locks, and latches, were typically handcrafted and designed to withstand the test of time, and they have remained as a testament to the ingenuity and creativity of the early American artisans who created them. Today, these original cast iron hardware pieces are highly valued by homeowners, collectors, and preservationists, as they offer a glimpse into the past and contribute to the unique character and charm of colonial homes.

Barber-Surgeon

Barber-surgeons, in addition to being able to cut hair, had some medical training and could treat wounds, set broken bones, and also perform minor surgery and dental work.

Gysbert Van Imbroch was the only medical professional in Wiltwyck, working as a barber-surgeon. He lived in this one room with his wife, Rachel, and their three children, Lysbet, Johannes, and Gysbert. During the Second Espous War in 1663, Rachel Van Imbroch, along with some other women and children, was captured by the Esopus and taken south to near modern-day Napanoch. Rachel managed to escape, came back to Kingston, and helped lead the search party to find the other captives. Rachel died in 1664, and Gysbert died in 1665. Upon Gysbert’s death, his possessions were inventoried. The original inventory was 12 pages long, and was translated by Dutch Scholar, Dingman Versteeg in 1898. Versteeg was hired in 1896 by Ulster County to translate all of the Dutch Colonial Records. The inventory includes a variety of items, such as kitchenware, clothing, furniture, and, notably, books! There are 60 different book titles in his inventory, covering a wide variety of topics, such as medicine, religion, history, and math. The children moved out of their house to live with family members, and the house was then rented out by 1666.

Learn more about Gysbert's Inventory.